The end of a year is often cause for reflection. At the end of 2022, investors who took part in this process might have been left scratching their heads, and having thoughts like “What just happened?” or “That’s not how markets are supposed to work!” Additionally, a cursory glance into 2023 provides investors with perplexing choices as they consider the possible outcomes and strategies for the year.

To sum up 2022 in a few words, investors were caught in a dramatic regime shift. Central banks were forced to rapidly turn-off the flow of cheap and easy credit, and hike interest rates as inflation became “non-transitory.” This switch wreaked havoc with risk appetites and asset valuations. The following highlight some of the high-end casualties:

- The S&P 500 was down 19.4%, the seventhworst year in its history

- The Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index (a broad-based fixed-income index used by bond traders and managers) had its worst year ever

- United States 10-year Treasuries had their worst ever year, and

- The third worst year ever for the standardized 60/40 (60% equities and 40% fixed income securities) portfolio

The last point is likely to have raised major concerns for conservative investors on two fronts. The first is that with equity valuations looking stretched going into 2022, investors would have felt confident that a sizable allocation to fixed income products would provide sufficient safety and insulation from falling share prices. History now shows that this was not to be the case. The second issue is that if that strategy did not work, for the reasons outlined below, how should they position themselves for the year ahead, especially considering that 2023 promises to be no less troublesome given serious geopolitical and macroeconomic concerns remain at the forefront?

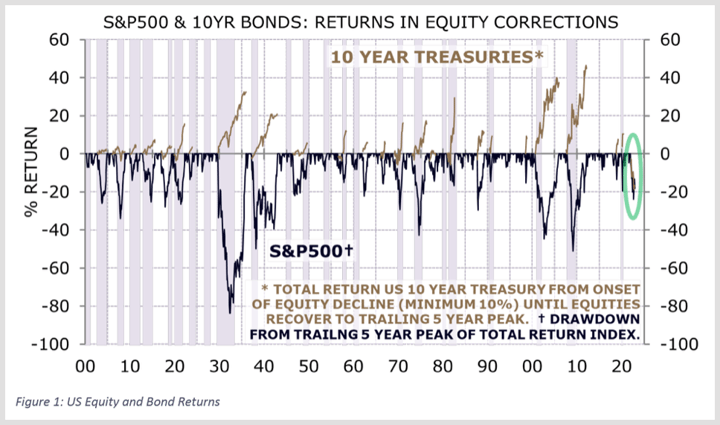

Why would investors have been comfortable thinking that a 60/40 portfolio would provide sufficient protection in the face of any stock market correction? The theory behind the strategy is the assumption that bond and equity returns are negatively correlated. In practice, this relationship means that when the environment is right for strong equity returns (typically a strongly growing economy), interest rates will generally increase. Due to the inverse relationship between bond prices and interest rates (yield) this situation generally results in lower returns for bonds. However, the inverse is also assumed to be true in that an environment of falling growth will result in lower equity returns that are mitigated by the positive capital effect of falling interest rates on bond prices (as central bank lower interest rates to stimulate a stuttering economy). However, 2022 saw both equities fall, and rates rise, as central banks were forced to respond to inflationary concerns by raising rates.

Indeed, the 60/40 strategy had worked very well for investors since the 1980s. However, investors may have become complacent and were unaware that the strategy’s success had several tailwinds, many of which abruptly stopped in the second half of 2022. Furthermore, some of the crucial tailwinds are unlikely to reappear in the short-to medium term. One such factor is the direction and magnitude of interest rate changes.

To cure the excessive inflation of the 1970s, interest rates worldwide started the 1980s in the high teens. Once inflation was brought under control in the early 1980s, the bond market went into a structural bull market that lasted for 40 years. This is because, for the past 3 decades, central banks have been able to keep lowering interest rates whenever the economy was weakened. Central banks were able do this as the developed world remained in a disinflationary environment due to several factors, including globalization and step changes in productivity driven by technology. The disinflationary environment ended in 2022 in the face of rising structural inflation. The vital takeaway from this situation is that for the first time in 40 years, investors faced material interest rate risk – the risk of price fluctuations in fixed coupon bonds due to changing interest rates.

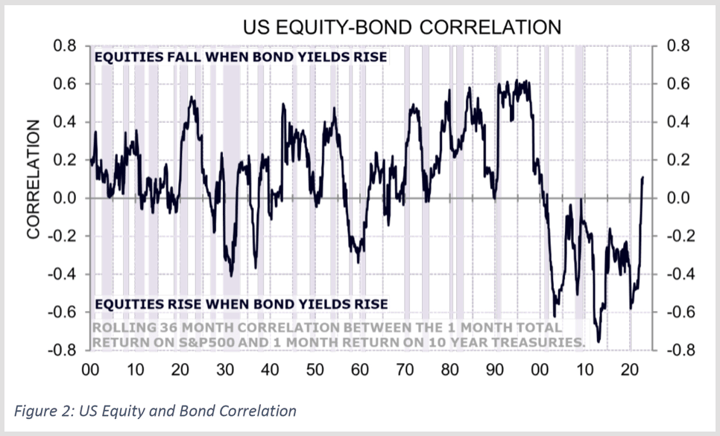

The failure of the 60/40 portfolio in 2022 was a direct result of the returns of bonds and equities becoming positively correlated. Promoters of the 60/40 portfolio would suggest that this outcome was a low probability event, a view supported by recent history. However, per Figure 2, faith in the negative correlation between equity and bond returns was misplaced as the last 20 years were an exception to the rule. In fact, there have been only three periods, with the two previous being short-lived, where the relationship has been negative.

Research into the equity and bond correlation (see articles from AQR[1] and Schroders[2]) highlights the relationship is not stable and is highly dependent on the regime in which markets find themselves. The upshot of the various research pieces suggests that the level of economic growth, the level and direction of inflation, and market volatility are the chief characteristics in determining the market regime. Therefore, investors need to take particular care in assessing these variables going forward.

Investors faced an environment of low inflation and moderate economic growth until the middle of 2022, meaning that the negative correlation between bond and equity returns held true. However, once inflation gained a stubborn foothold and economic growth remained high because of post-COVID stimulus, the market switched to a regime where the more traditional positive correlation would rule. That is, interest rates were rapidly lifted by central banks off their all-time lows, with the duration effect (raising rates leading to lower bond prices) swamping the benefits of rising yields. This change coincided with equities coming off their post-pandemic peaks due to higher discount rates and emerging earnings uncertainties.

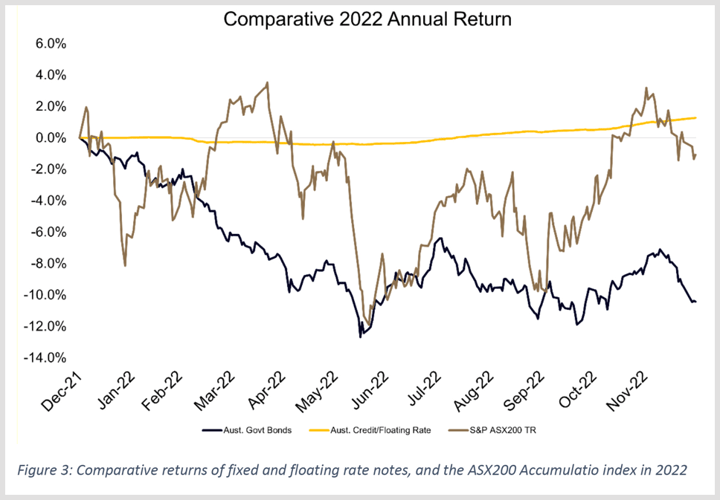

Importantly, it was not all doom and gloom in the fixed income markets. Fixed income is a broad term that encompasses a range of strategies, including those that avoid interest rate risk in their portfolios by investing in floating rate securities. The floating rate world is typically defined as “credit” as opposed to the fixed rate world of government bond investing. Credit managers are thereby a subset of fixed income managers who specialize in producing portfolios containing securities with little or no interest rate risk while managing an appropriate level of credit risk.

Interest rate risk disappears because the value of a floating rate security is not directly affected by changing interest rates. However, floating rate securities are not risk-free, rather the investors face credit risk, that is the risk that the issuer will be unable to make ongoing coupon payments or return the face value of the bond at maturity. Investors also have to consider spread risk, which is the risk that the market decides to increase or decrease the spread it charges over government bonds for different levels of credit risk.

Figure 3 provides an illustration of the both the pain and volatility that fixed rate bond holders (Aust. Govt Bonds) and equity holders (ASX200 Total Return) experienced compared to floating rate holders in 2022. As can be seen, a portfolio with a significant allocation to floating-rate assets would have offered the greatest level of stability in 2022.

In addition to nullifying interest rate risk, credit manager can adjust the exposure of the portfolio to changes in market pricing (credit duration) and the credit quality of their portfolios to match future market conditions. Quality is adjusted by increasing, or decreasing, a fund’s exposure to higher or lower rated securities.

For instance, if economic conditions are expected to decrease – an environment where equities will be falling – a credit manager would increase their investment grade exposure (BBB and above) at the cost of their non-investment grade (lower than BBB). While this in turn will also impact yield – a higher rated product will pay a lower coupon due to the lower risk associated with holding it – it leaves the portfolio better placed to withstand a deterioration in market pricing.

The other opportunity credit managers have to de-risk their portfolio is to shorten the average maturity of assets in their portfolio (credit duration). This aim is achieved by investing in short-dated securities (6-12 months) over long-dated securities (3 plus years). The less time a security has till maturity, the less its price is impacted by changes in market pricing. Therefore, in an environment where the market appetite for risk is expected to deteriorate, a portfolio with a lower credit duration will provide a better outcome.

Of course, the preceding paragraphs were primarily written with the benefits of hindsight, a luxury that investors do not possess. So what are investors to do going forward? To quote Chief Investment Strategist for Tangent Capital Bob Rice, “the old 60/40 portfolio did the things that clients wanted, but those two asset classes alone cannot provide that anymore. It was convenient, it was easy, and it’s over.”

The first step is to assess what market regime is likely to dominate in the coming years. As explained earlier, this choice will great affect the equity-bond return correlation. At the time of writing the consensus view is that while inflation may decline, it will remain elevated and above central bank targets, with economic growth also slowing. These factors create an opportunity for the positive correlation between equities and bonds to remain intact. The persistency of a positive correlation then has implications for investors who are not quite prepared to abandon the 60/40 asset allocation framework.

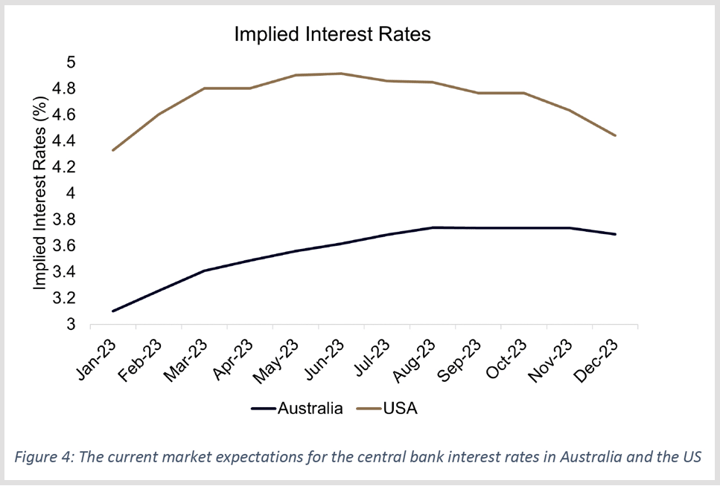

If an investor does wish to maintain a healthy allocation to fixed income products to offset potential volatility within equities, they need to consider how they allocate between interest rate and credit risk exposure, as both can perform different roles within a portfolio’s strategic asset allocation. With a material rise in interest rates during 2022, government bond markets now offer some yield to help protect against further rises in interest rates and, as per Figure 4, the market is expecting a reduction in rate levels heading into 2024. However, because there is still considerable uncertainty about whether central banks will be able to bring inflation back into their target range, the outlook for interest rate markets is still likely to be quite volatile.

The volatility of 2022 provided plenty of issues for investors to consider, including how to allocate within the fixed income market. Through investing in floating rate fixed income assets, especially those with a low credit risk, you’re likely to achieve a favourable result in a rising rate environment. Crucially, exposure to floating rate securities will reward investors, yet not expose them to unnecessary volatility.

By Dr Matthew Oldham, Head of Data Analytics