What impact has Japan’s monetary policy had on the world economy over the past several decades?

Japan’s monetary policy changes are one of the key factors explaining both the country’s super-boom combined with huge asset price inflation in the 1980s, and the subsequent bust and long period of underperformance since. Monetary policy changes also set the scene for Japanese institutional investors to become major participants in overseas government bond markets, especially the Australian government and semi-government bond markets, from the early 1990s. Now, as the Bank of Japan is starting to tweak monetary policy tighter, potentially creating the prospect of a positive return from investing at home for Japanese investors for the first time in 40 years, there is growing concern about what impact a potentially large-scale exit from Japanese offshore bond holdings may have. This article will examine how monetary policy influenced Japan’s boom, bust and changing appetite for overseas assets.

The booming 80s

In late December 1989, Japan’s Nikkei share index peaked at an all-time high of 38,916, with PE ratios on many large stocks at more than 100 times. At the peak, one square mile of land in central Tokyo was worth the same as the entire US state of California, and Tokyo golf club memberships topped the equivalent of $US250,000. It was a boom and accompanying asset price bubble like no other, and in its later stages was fueled by monetary conditions that were set far too easy for far too long.

Over three decades prior, Japan had transformed from an agriculture based developing economy to a manufacturing powerhouse. By the late 1980s Japan was the second biggest economy in the world after the United States.

The way Japanese businesses were structured helped to fuel Japan’s success through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Japanese businesses followed the “Keiretsu” model, where closely related businesses took majority shareholder interests in each other, often involving a bank in the group. This created a platform for Japanese businesses to access capital at cheap rates, which in turn allowed them to spend on research and development on a scale and price that overseas competitors could not match.

As a result, Japanese products were often more advanced, better produced and cheaper than the products of rival companies overseas. Adding to the advantage for Japanese companies, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry permitted the flow of easy credit to the Keiretsu and provided protection against foreign competitors through the 1970s and 1980s.

The resulting extraordinary Japanese business success in world markets prompted speculation in Japanese shares in the 1980s and extended to property speculation, often funded by Japan’s banks. Commercial land prices tripled in the second half of the 1980s and highly priced property formed the collateral for the banks to lend more.

During the late 1980s, central banks globally were generally concerned about inflation that had stayed too high for too long. In addition to high inflation, the Bank of Japan had the extra concern that it could no longer ignore the extraordinary Japanese asset price bubble that had continued to inflate, even through and after the US stock market crash in October 1987.

When it started, the Bank of Japan’s policy response was aggressive. It raised the official interest rate from 2.50% to 4.25% in 1989 and then pushed the rate up further to 6.00% in 1990, continuing to tighten even as the economy and asset prices were collapsing. The aggressive policy tightening was particularly painful because the economy had been force fed on easy credit for so long, leading to lax banking practices that rapidly became exposed. Analysts have pointed to the Bank of Japan tightening policy too much, and then maintaining that policy setting for of too long in the early 1990s, as one cause of Japan’s prolonged recession.

The long recession

The Bank of Japan’s aggressive policy tightening in 1989 and 1990 caused sharp falls in asset prices, destroyed significant bank loan collateral, and led to the unravelling of Keiretsu business arrangements. The quick slide into recession also laid bare issues for Japan’s long-term growth prospects that had been masked in the 1980s boom.

Compared to the shrinking working age group, Japan’s significant and growing proportion of individuals over the mandatory retirement age of 65 tended to save more and spend less of their income. The working-age cohort was constrained in size due to low levels of female labor-force participation and very low net immigration to Japan. Another factor limiting participation was Japanese employers’ practice of paying higher salaries based on seniority. As a result, relatively expensive older workers were far less likely to be re-employed if they found themselves unemployed.

Japan’s total population would also start to fall in the 1990s. These demographic and employment factors would make it hard for the Japanese economy to grow in the best of circumstances and contributed towards keeping Japan in near permanent recession for a quarter century beyond 1990.

Poor banking practices were exposed with the destruction of loan collateral caused by collapsing asset prices – the Nikkei fell 43% in 1990 and land prices fell more than 40% through the 1990s. The bursting asset price bubble led to banks accumulating bad loans and an almost immediate increase in bank failures that would eventually peak in 1998, when more than 180 Japanese banks collapsed.

At the time, any official capital injection that might have helped the banks to struggle on was resisted by the authorities as it was regarded as a moral hazard. The notion of moral hazard was reinforced by manufacturing companies arguing to the Government that they had received no capital injections when they needed them, so why should the banks receive any special assistance. The attitude towards capital injections would eventually change in the 2000s and contribute to Japan’s later slow recovery.

In the 1990s, Japanese banks faced diminishing collateral value on loans and mounting bankruptcies among their corporate and personal customers, making meeting prudential capital adequacy requirements onerous. The international Basel 1 capital requirements enacted at the time required banks to hold 8% capital, regardless of economic conditions. Japan’s banks found raising capital to meet prudential requirements hard and responded by reducing loans. Riskier small and medium-sized businesses that often provide the new products and vibrancy to lift an economy out of recession suffered as the banks tried to cut their riskiest loans.

As a result, the Japanese economy was beset by declining bank lending at the same time deteriorating economic conditions were reinforcing the already high tendency of Japanese businesses and households to save rather than spend. Economic growth and prices in Japan entered a cycle of decline that needed a circuit breaker from effective monetary and fiscal expansion to offset the factors reducing private sector spending.

What support that was provided in the 1990s from monetary policy easing and increased government spending was largely ineffective. The Bank of Japan was slow to cut interest rates and provide liquidity support, pushing the economy into a protracted period of price deflation. Even when nominal interest rates were eventually cut, real interest rates – adding in deflation – remained high.

Fiscal policy initiatives in the early years of the recession revolved around more spending on public investment on roads and bridges, not income support initiatives for households and businesses that might have provided a stronger multiplier effect and boost to aggregate demand. The new roads and bridges were often in rural prefectures, meeting local political, rather than economic, imperatives. Given the rural road system was already of high standard, the new infrastructure was under-used and the economic multiplier from the road and bridge building program was low. It was said at the time that Japan was good at building bridges to nowhere.

These inadequate monetary and fiscal policy responses made it hard for Japan to escape recession and deflation, especially when the private sector was under constant pressure to try and save more and spend less.

One outcome of the long recession and deflation was that burgeoning Japanese savings sought higher returns overseas. Japan’s conservative institutional investors started a slow increase in asset allocation away from local bonds and towards higher yielding, high quality government bonds outside Japan. US, Australian and New Zealand bonds became popular. Japanese investment in Australian government and semi-government securities would build through the 1990s to a peak of around 15% of total bonds on issue.

In response to their “lost decade”, Japan was an early adopter of very low interest rates combined with unconventional monetary easing (asset purchases from banks to boost their liquidity) from 2001 to 2006. Ultra easy monetary conditions slowly helped Japan to lift from its long recessionary phase and by 2003 Japan’s annual GDP growth rate was up to 2% – not a fast growth rate, but a sharp improvement on the declining GDP over the previous two decades.

Escaping the long recession

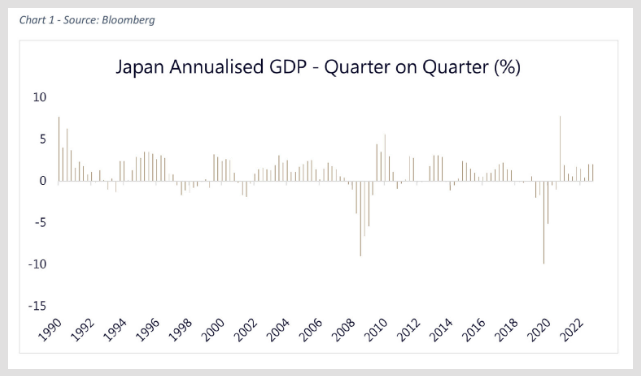

While the ultra-easy monetary conditions of the early 2000s combined with some fiscal easing allowed Japan to lift out of recession, the improvement was a stop-start affair. Japan’s high budget deficit became a concern, prompting budget saving initiatives often in the form of tax increases that were granted with little regard to the state of the economy. As a result, promising economic recovery phases were cut short by budget-saving-dictated tax increases. (Chart 1)

It was not until Shinzo Abe was elected Prime Minister for a second time in 2012 that a suite of policy initiatives was adopted to tackle most of the factors inhibiting Japanese growth and any return to modest inflation. Known as the three arrows and dubbed “Abenomics”, the policies involved:

- government spending initiatives to boost aggregate demand

- very easy monetary conditions including a return to asset purchases or quantitative easing, and

- regulatory changes to help make Japanese businesses more competitive in global markets.

The regulatory changes would extend to trying to combat some of Japan’s most growth-inhibiting practices, including attempts to address Japan’s low female participation rate in the workforce. Also, Japan’s longstanding resistance to migrant workers was tackled by establishing special economic areas where overseas workers could be employed more easily.

The Economist magazine described Abenomics as “a mix of reflation, government spending and a growth strategy designed to jolt the economy out of suspended animation that has gripped it for more than two decades”.

Abenomics was partially successful in its ambitions. Over the past decade Japan’s growth rate has improved and at a current rate of close to 2% y-o-y, is better than growth in the US or Europe. Japanese companies have become more competitive and improved profitability, helping the Nikkei index rise more than 24% so far this year against 16% for the high-flying US S & P 500. Despite this improvement, the Nikkei index still trades 16% below the record set back in December 1989.

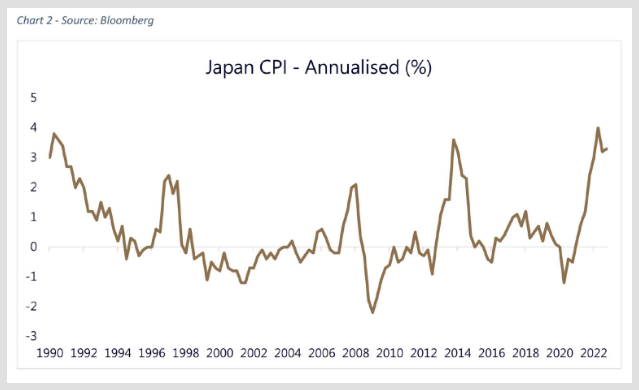

Japan has also escaped deflation and returned to modest inflation (Chart 2). At 3.3% y-o-y in June 2023, Japan’s inflation rate is higher than US inflation at 3.0%.

However, the legacy of Japan’s low growth deflationary past still influences Japanese policymakers. There is a tendency to leave monetary conditions too easy for too long given Japan still has significant headwinds reducing its growth prospects being:

- Japan’s population continues to age and fall

- the changes to female participation in the workforce and immigration have been limited, and

- Japan’s savings ratio remains very high.

The Bank of Japan has retained a negative official interest rate even in face of higher inflation and as its central bank peers have lifted their official interest rates by 4 percentage points and more. It has also tried to retain longstanding yield curve control where it targets the yield on the 10-year Japanese government bond at around zero with tolerance of 50bps either side of zero.

However, higher inflation has placed pressure on the Bank of Japan’s yield curve control with the market pressuring the 10-year bond yield to push above 0.50%. In late-July 2023, the Bank of Japan conceded that it could not hold the 10-year bond yield below 0.50% and would tolerate brief episodes of trading above that yield.

As at August 14th of this year, the 10-year Japanese bond yield at 0.61% is up 15bps over the past month, indicating that the market is continuing to test the Bank of Japan’s commitment to easy monetary conditions.

The signs that Japanese interest rates are finally rising is reinforcing a change in asset allocation by Japan’s institutional investors towards bringing money home and investing at positive return in Japanese bonds. The move is causing some concern that there could be a large exit from their investment in overseas bonds, including their holdings of Australian bonds. If a significant enough sell-off occurs, the resulting weakness in the Australian bond market has the potential to exacerbate a slowdown in the domestic economy and keep our interest rates higher for longer.

This concern is perhaps mitigated by the fact that Japanese bond yields sit well below yields in Australian bonds and will stay well below that given it is likely to be a very slow turn towards tighter monetary conditions in Japan. However, it remains a watchpoint for investors globally given the potential technical impact to pricing from a meaningful reversion to domestic investment by Japanese investors.