Originally published on Livewire

Economy-wide measures of inflation come with inherent flaws. This is through no fault of the...

Originally published on Livewire

Economy-wide measures of inflation come with inherent flaws. This is through no fault of the...

Originally published on Livewire

Economy-wide measures of inflation come with inherent flaws. This is through no fault of the agencies charged with measuring inflation (domestically it’s the Australian Bureau of Statistics) but more a recognition that there is no magical rate that will accurately represent the change in the cost-of-living expenses for the average consumer.

Despite their flaws, inflation measures (headlined by the Consumer Price Index) play an important role in monetary policy decision making; a key mandate of central banks globally is maintaining a moderate level of inflation, including the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) which has an inflation mandate of 2% - 3%.

Monetary policy impacts the level of interest rates, which in turn defines how much investors can expect to earn on their savings. In a low rate environment, savers are effectively penalised in the interest of supporting growth, leaving them with limited options for earning a suitable return on their capital.

To combat the high inflation environment of the late ’70s/early ’80s, the central bank inflation mandate was achieved by keeping interest rates in the range of 14% - 18%. However, in the persistently low inflation world post-GFC, the issue has become creating conditions for inflation to grow through keeping interest rates lower, i.e. in the range of 0.1% - 3%.

The RBA has been very clear about what they need to see before considering any change to the current level of interest rates; a rise in wages. Average weekly earnings have been anemic over the past 5 years, with the wage price index rising at 2.0% p.a. By keeping interest rates lower, the RBA hopes that the resulting stimulation through investment will drive growth and with it wages for the average Australian. While over time this program may be successful, in the interim many Australians could find themselves in a situation where:

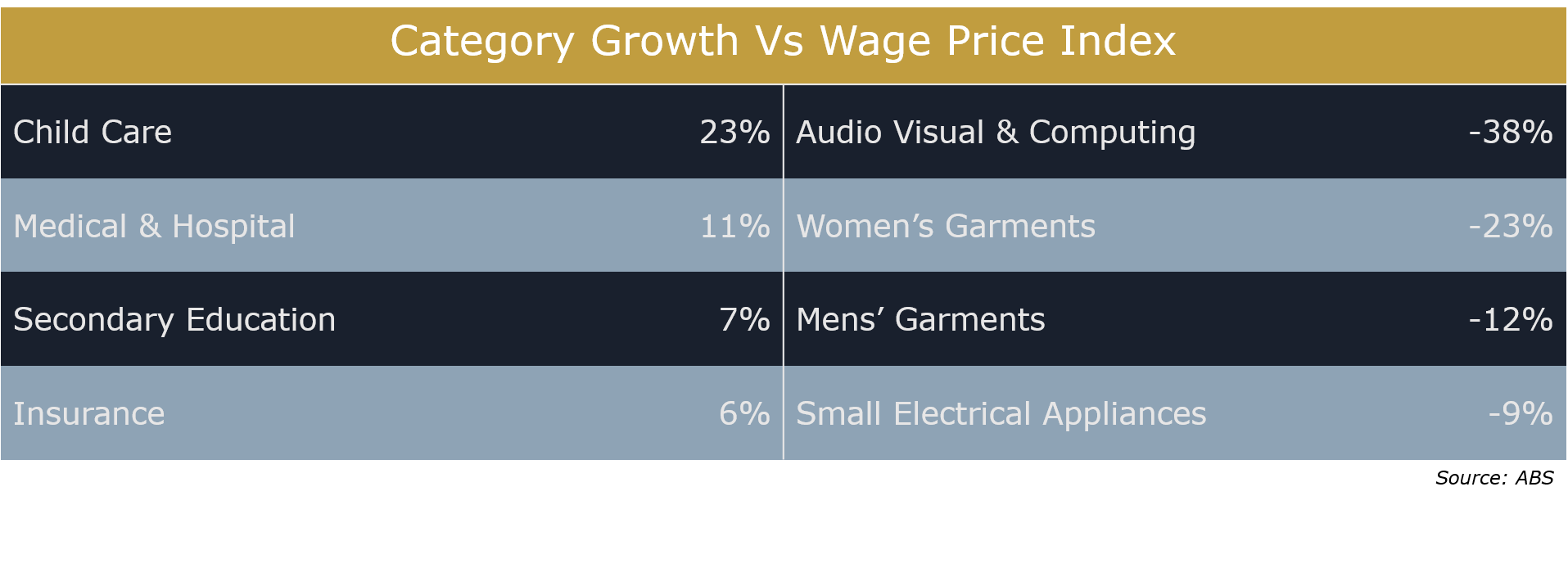

A look at the data produced by the ABS on inflation and wages over the past 5 years highlights some interesting examples that speak to this second point.

Over the last five years buying a new computer, t-shirt or appliance has become considerably cheaper versus the average wage. However, education, health and insurance have grown in excess of average wages.

Cheaper electronics, clothes and toasters are handy, but for the most part, they fall into a household’s discretionary spending bucket. However, items like health, education and insurance are typically non-discretionary. As a result, cost of living pressures have grown for many Australians.

These pressures have compounded for those relying on a fixed income from bank deposits to pay for everyday, non-discretionary expenses. For those that fall into this category, the need for a regular income combined with the stability of capital from their portfolio has never been higher. But due to low interest rate policy and competition for investments with yield, it has also never been harder to find low-risk products that meet this requirement.

Many of the traditional options for yield and stability such as government bonds and bank term deposits no longer provide sufficient return, particularly in light of the cost of living challenges discussed above, but credit investments are a viable alternative. Credit is a very broad universe and can be used to describe a large range of investments from highly liquid senior bonds issued by banks through to private bespoke lending strategies.

The variety of options and strategies available within credit markets creates structural inefficiencies a skilled manager can consistently exploit to provide healthy income without sacrificing a prudent approach to risk.

Traditional asset classes offer too little prospective return or too much potential volatility for investors trapped between rising costs for non-discretionary items and a structurally lower return on their capital, but there are solutions available through credit investments.